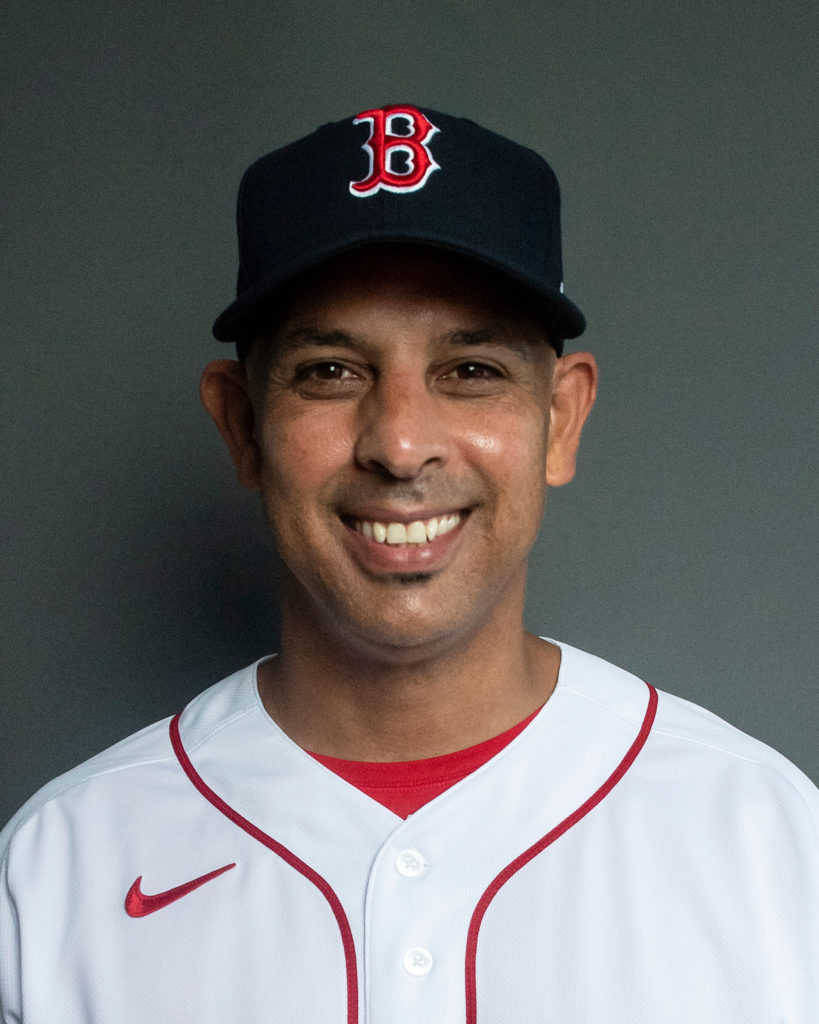

Chief Baseball Officer Chaim Bloom is putting together a New Look roster in Boston. Photo by Billie Weiss/Boston Red Sox/Getty Images

By ART MARTONE

When Red Sox chief baseball officer Chaim Bloom first addressed the

media at the start of spring training, he was greeted with this

observation from long-time WBZ Radio reporter Jonny Miller:

I haven’t seen the fans or the media be this pessimistic about the Red

Sox since 1964.

Red Sox beat reporter Jonny Miller welcomes Chaim Bloom to his second Sox spring training with a brutally honest question.#RedSox | #ChaimBloom | #SpringTraining | https://t.co/qFBBXwiFRL pic.twitter.com/vMjy0Ydocf

— NESN (@NESN) February 21, 2021

Wait. What?

1964?

Why 1964?

There may — or may not — be reason to think this Red Sox season will

be as bad as, or worse than, last year’s train wreck (we’ll get to that in a

minute), and there are still recent off-field wounds that haven’t healed.

But where did 1964 come from? Why did Jonny declare that to be the

last time such a dark preseason cloud hung over Boston baseball?

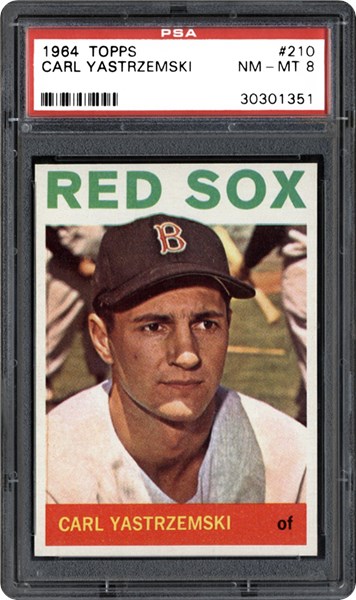

Here’s my disclaimer: I was 8 years old on Opening Day 1964, turning 9

two months into the season, and it was the year I fell in love with

baseball. The first year I followed the team day by day, the first year I

collected baseball cards, the first year I went to a game at Fenway Park.

Because of all that, I’m intimately familiar with those sons of Lou

Clinton and Arnold Earley.

But blind childhood affection isn’t why this baffles me. Consider . . .

— The Sox entered 1964 coming off a 76-win season, which is basically

the same year they’d been having over and over since the late ’50s.

(1963 was, in fact, the third straight time they’d finished with exactly 76

victories.) Mediocre? Yes. But not terrible.

— They had on their roster the defending American League batting

champion (Carl Yastrzemski), the defending RBI champion (Dick Stuart),

a returning 20-game winner (Bill Monbouquette) and arguably the best relief pitcher in baseball (Dick Radatz). They also had an exciting, charismatic rookie (Tony Conigliaro) who was a local boy to boot. They

didn’t have a whole lot beyond that but they did have players worth

watching.

— It was well-known — and I did know, even at age 9 — that the Sox had

talent in the farm system bubbling its way up. They had a powerhouse

team that included three future regulars at Class A Wellsville in 1963,

and all their minor-league affiliates had winning records in 1964. By

1967 (remember?), we would discover just how much talent there was.

What I’m saying is that while nobody expected the Red Sox to win the

pennant or even contend for it in 1964, there was no real reason to

suspect ’64 would be much different than the seasons just past. And

thus no reason for a spate of unprecedented preseason depression.

So I repeat: Why 1964?

I might have agreed with Jonny if he’d said `since 1965.’ It was in 1964 after all that the Sox got off their 76-win treadmill and plummeted to 90 losses, their worst showing in 32 years. Or `since 1966,’ considering they wound up losing 100 games in ’65. That’s the kind of stuff that’ll fill the pessimism tank pretty quickly, no matter how many good players or how much promising young talent you have.

Or, jumping ahead, why not 1981? The 1980-81 offseason was when the Red Sox went all in on dismantling the 1970’s SuperTeam that fell juuuussst short of smothering the Curse of The Bambino nonsense before it took its first breath. They got a fairly decent return when they traded Rick Burleson, about 20 cents back on the dollar when they traded Fred Lynn, and nothing at all for Carlton Fisk, whom they let escape to free agency through front-office ineptitude. Man, Opening Day karma was a bitch. It was a stunning case of executive malpractice by Haywood Sullivan and crew, and if you think people are mad at Sox ownership now, well, you shoulda seen it then.

No one, and I mean no one, was in love with the Old Towne Team heading into 1981.

Yeah, yeah, I know. Enough ancient history. All right, then. Remember

2013? That was the year after the Bobby V. fiasco, the year after the

salary dump trade of Josh Beckett, Adrian Gonzalez and Carl Crawford

to the Dodgers for a collection of flotsam and jetsam, the year after the

team’s second last-place finish in 80 years. (It would become rather

commonplace for the Red Sox to finish last in seasons ahead — usually

between championships — but it was pretty unique in 2012.) They

bolstered their roster with a bunch of mid-level free-agent signings, but

it was assumed heading into ’13 that a return to contention was at least

a few years away. Not many were embracing the Sox that spring, not

after their stunning September collapse in 2011 and odorous performance in 2012.

Clearly, 2021 isn’t the first time people are down on the Red Sox as a

new season dawns. But should they be?

There’s no question the current Sox are still paying the public-relations

price for trading Mookie Betts, and they should. There’s no excuse,

none, for a team of means to surrender such a generational talent for

financial reasons, which — in the absence of any hard facts (like the

certain knowledge he would refuse to stay here once he became a free

agent) — is what we’ve been led to believe. If you remain mad at that,

you’ve got reason.

And then there was whatever you want to call what happened in 2020.

Me, I like to think of it as an experiment: What would the result be if

you attempted to play a major-league season, even an abbreviated

one, with a minor-league pitching staff? Wasn’t pretty, that’s for sure.

All legitimate reasons to be, as Jonny said, pessimistic. Not just at the

team’s on-field prospects, but at the way it’s being run.

On the other hand . . .

They did get a pretty good haul for Betts and David Price. Not enough

to justify trading Mookie, no; that wasn’t possible. But Alex Verdugo

looks like a player, and Jeter Downs and Connor Wong could be useful

in the days to come. Bloom has also made a number of under-the-radar

acquisitions, not just in free agency but in trades, that have expanded

the organization’s talent base far beyond what it was when play

resumed last July. The everyday lineup — while it may be in constant

flux due to the collection of multi-position pieces — should be

productive. (It was pretty productive last year, finishing fifth in the

league in runs scored even with offensive black holes at second base

and DH.) And somewhere in the pile of arms down at Fort Myers could

be the makings of a decent enough pitching staff, which is really the key

to whatever success they will or won’t have.

Turning points in history are easy to see in retrospect. I know Jonny Miller and I like him, but I’m certain he chose 1964 because, when you look back on it, that was the season the Red Sox morphed into something different than what they’d been. After winning the American League pennant in 1946 they’d been on a long, downward glide from champion to contender to good to okay to so-so. In 1964, without anyone really seeing it coming, they fell through the floor. They would lose 280 games in the 1964-65-66 span, and today we know that; today, we know where the line between middling and awful was drawn. But in the spring of 1964 they were seen as the same old Sox, picked to finish seventh – again – in the then-10-team American League

by Sports Illustrated.

Conversely, sometimes we detect lines that aren’t there. Those ’81 Sox, who were in such bad odor? They played at an 88-win pace in that strike-shortened season, then won 89 – and stayed in the race with two vastly superior opponents (Milwaukee and Baltimore) until the final weeks – in 1982. And, of course, we all know what happened in 2013. Boston Strong. World Series champions. Those no-name mid-level free agents became October heroes Jonny Gomes and Mike Napoli and Koji Uehara and Shane Victorino.

Where are we today?

Hell, we don’t know. Nobody does. The Red Sox are certainly operating

differently under Chaim Bloom than they did under Dave Dombrowski,

but what does that mean going forward? It’s tough enough to see the

truth in the present.

Seeing it in the future? Impossible.

Yes, there are reasons to be pessimistic about the current Red Sox. Just look back to where they were in 2018 – 108 wins, an 11-3 blitz through the postseason, virtually every key player under the age of 30 — and compare it to now, three short years later. How in the world did we get from there to here? And there’s no shortage of people who aren’t big fans of the Sox’ new team-building philosophy, especially those who believe big-market teams have a moral imperative to spend, spend, spend and spend some more.

And there are reasons to be not so pessimistic. Old friend John Tomase

lays out that case as well as anyone.

You know the old saying: That’s why they play the games.

It’s as true now as it was in 1964.

Art Martone wrote a Red Sox-based Internet baseball column for

projo.com, for which he was named Best Sports Columnist by Boston

Magazine in 1998. He also wrote about baseball for the Providence

Journal and has had Red Sox material published in several baseball-only publications. He worked at the Journal from 1974 to 2009 and was

Sports Editor from 2000 until leaving in 2009 to become Managing

Editor of NBC Sports Boston’s Web site. He remained there until his

retirement in 2019.